Imagine a rash that heals, the scabs fade, and the skin looks normal again—but the pain never leaves. For people with postherpetic neuralgia, this lingering pain can persist for months or even years after shingles has resolved, turning a temporary viral illness into a long-term neurological condition.

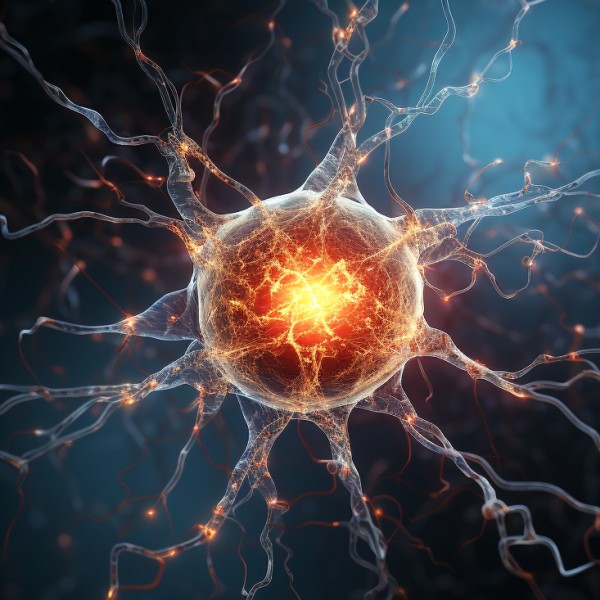

Postherpetic neuralgia (PHN) is the most common chronic complication of shingles. It occurs when nerve damage caused by the varicella-zoster virus results in persistent neuropathic pain in the area where the shingles rash once appeared. Although the skin may recover, the affected nerves continue to send pain signals long after the infection has ended.

PHN is not rare, especially among older adults, and it represents one of the clearest examples of how viral injury can permanently alter nerve function.

What Causes Postherpetic Neuralgia?

Postherpetic neuralgia develops as a consequence of nerve injury during shingles.

The varicella-zoster virus—the same virus responsible for chickenpox—remains dormant in sensory nerve ganglia after the initial infection. Years or decades later, it can reactivate as shingles (herpes zoster), traveling along sensory nerves to the skin and causing a painful, blistering rash.

In some individuals, the inflammation and direct viral damage disrupt the nerve fibers themselves. This damage may involve:

- Loss of normal inhibitory signaling

- Abnormal spontaneous firing of pain fibers

- Structural injury to sensory neurons and dorsal root ganglia

When the nerves fail to heal properly, pain persists even after the virus is no longer active. This chronic pain state is postherpetic neuralgia.

Risk Factors

Not everyone who develops shingles goes on to develop PHN. The risk increases with:

- Advanced age (especially over 60)

- Severe or prolonged shingles pain

- Extensive rash

- Delayed antiviral treatment

- Compromised immune function

Older nerves are more vulnerable to injury and less likely to recover fully, which explains why PHN disproportionately affects older adults.

How Postherpetic Neuralgia Feels

Postherpetic neuralgia is a form of neuropathic pain, and its symptoms reflect abnormal nerve signaling rather than ongoing tissue damage.

Common pain descriptions include:

- Burning or searing pain

- Electric shock–like sensations

- Stabbing or shooting pain

- Deep aching or throbbing

- Extreme sensitivity to light touch (allodynia)

Even clothing brushing against the skin or a light breeze can trigger severe discomfort. Pain is typically confined to the same dermatome—the band of skin served by the affected nerve—where shingles occurred.

Other Associated Symptoms

In addition to pain, patients may experience:

- Numbness or reduced sensation

- Itching (sometimes severe)

- Sleep disturbance

- Fatigue

- Anxiety or depression related to chronic pain

These secondary effects often contribute as much to reduced quality of life as the pain itself.

How Long Does Postherpetic Neuralgia Last?

By definition, postherpetic neuralgia persists for at least three months after shingles rash healing. In practice, duration varies widely:

- Some cases resolve within months

- Others persist for years

- A subset becomes lifelong

Early treatment of shingles reduces the risk and severity of PHN, but once established, the condition can be difficult to reverse completely.

Diagnosis

Postherpetic neuralgia is primarily a clinical diagnosis.

Diagnosis is based on:

- History of shingles

- Persistent pain in the same distribution as the prior rash

- Neuropathic pain characteristics

Imaging and laboratory tests are usually unnecessary unless symptoms are atypical or another neurological condition is suspected.

Treatment Options

There is no single cure for postherpetic neuralgia, but multiple treatments can reduce pain and improve function. Management typically focuses on symptom control rather than nerve repair.

Medications commonly used include:

- Gabapentin or pregabalin to reduce abnormal nerve firing

- Tricyclic antidepressants (such as amitriptyline) for neuropathic pain modulation

- Serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs) in some patients

- Topical lidocaine patches to reduce localized pain

- Capsaicin patches or creams, which may decrease pain over time by desensitizing nerve endings

Opioids are generally avoided or used cautiously due to limited benefit and high risk in chronic neuropathic pain.

Non-Pharmacologic Approaches

Some patients benefit from adjunctive therapies, including:

- Cognitive behavioral therapy for pain coping

- Physical therapy to maintain mobility

- Gentle desensitization techniques

- Sleep optimization and stress reduction

While these approaches do not cure PHN, they may improve daily functioning and pain tolerance.

Prevention: The Most Effective Strategy

The most effective way to reduce postherpetic neuralgia is preventing shingles in the first place.

Shingles vaccination significantly lowers the risk of:

- Developing shingles

- Severe shingles

- Postherpetic neuralgia

Vaccination is especially important for older adults, who face the highest risk of long-term nerve pain.

Why Postherpetic Neuralgia Matters

Postherpetic neuralgia illustrates how a brief viral reactivation can result in lasting neurological injury. It is not simply “pain that lingers,” but a chronic condition driven by damaged sensory nerves and altered pain processing.

For patients, PHN can interfere with sleep, concentration, mood, and independence. For clinicians, it highlights the importance of early antiviral treatment for shingles and aggressive pain management when nerve injury is suspected.

Postherpetic neuralgia reminds us that when nerves are damaged, healing is not guaranteed—and prevention and early intervention remain the most effective tools.

Further Reading

- Interventional Treatments for Postherpetic Neuralgia: A Systematic Review.

- A systematic review and meta-analysis of risk factors for postherpetic neuralgia.

- Post-herpetic Neuralgia: a Review.

- Investigational Drugs for the Treatment of Postherpetic Neuralgia: Systematic Review of Randomized Controlled Trials.

- Trigeminal Postherpetic Neuralgia: From Pathophysiology to Treatment.

- Therapeutic Strategies for Postherpetic Neuralgia: Mechanisms, Treatments, and Perspectives.

- Analgesic Treatment Approach for Postherpetic Neuralgia: A Narrative Review.