Imagine growing up with vision that never quite sharpens, balance that feels unreliable, and energy levels that swing unpredictably—without an obvious explanation. For people with De Morsier syndrome, these challenges often begin early in life, quietly shaping development long before a diagnosis is made.

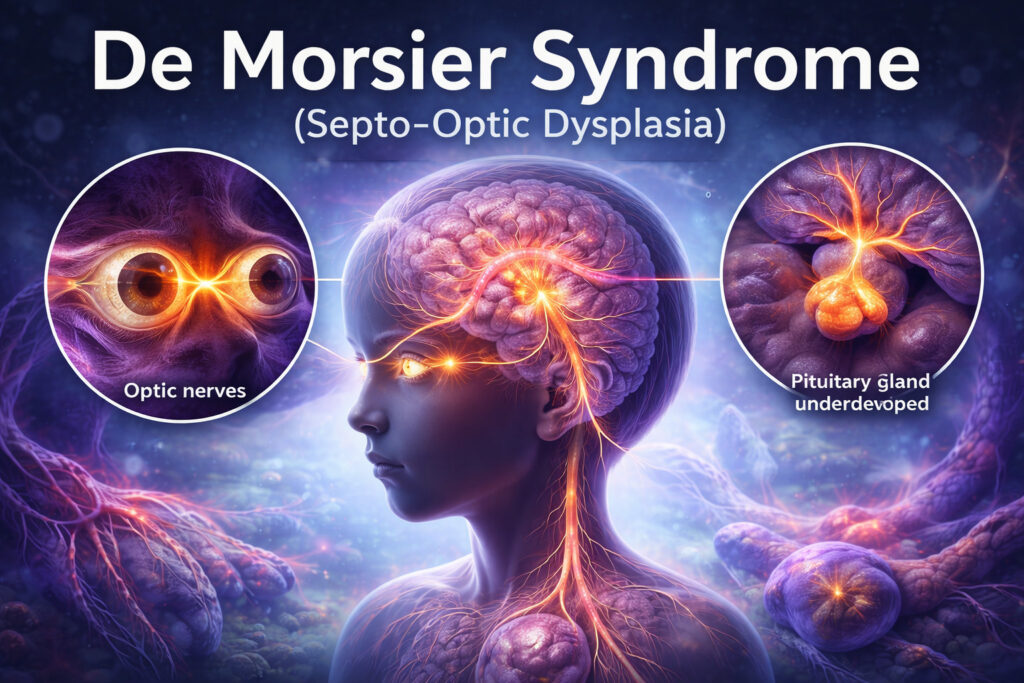

De Morsier syndrome—more commonly known as septo-optic dysplasia (SOD)—is a rare congenital neurological condition that affects early brain development. It is classically defined by a triad involving underdevelopment of the optic nerves, abnormalities of midline brain structures, and dysfunction of the pituitary gland. Not every individual has all three features, which is one reason the condition can be overlooked or misclassified.

Although it is not primarily a neuropathy, De Morsier syndrome frequently involves the nervous system in ways that affect vision, coordination, sensation, and hormonal regulation—sometimes creating secondary nerve-related symptoms that evolve over time.

What Causes De Morsier Syndrome?

De Morsier syndrome arises from disrupted brain development during early pregnancy, typically in the first trimester. The exact cause is often unknown, but contributing factors may include:

- Sporadic genetic mutations (most cases are not inherited)

- Abnormalities in early embryonic signaling pathways

- Prenatal environmental factors such as young maternal age, vascular disruption, or certain exposures

Unlike many inherited metabolic or neurodegenerative disorders, De Morsier syndrome is not usually progressive in the classic sense. However, its consequences can unfold gradually as developmental demands increase.

The Core Signs of De Morsier Syndrome

The condition is traditionally defined by three key findings:

- Optic nerve hypoplasia

One or both optic nerves are underdeveloped, leading to reduced visual acuity, visual field loss, or blindness. - Midline brain abnormalities

Most commonly absence or malformation of the septum pellucidum, a thin membrane separating the brain’s lateral ventricles. Other midline structures may also be affected. - Pituitary hormone dysfunction

The pituitary gland may be underdeveloped, leading to deficiencies in growth hormone, cortisol, thyroid hormone, or antidiuretic hormone.

An individual may have only one or two of these features and still meet criteria for the diagnosis.

Nervous System Involvement and Neurological Symptoms

Although De Morsier syndrome is not a peripheral nerve disorder, neurological involvement is common and clinically important.

Patients may experience:

- Visual impairment affecting spatial awareness and coordination

- Balance difficulties and abnormal gait

- Developmental delay or learning difficulties

- Seizures (in a subset of patients)

- Reduced temperature regulation or fatigue related to hormonal imbalance

Some individuals report sensory processing issues or pain syndromes later in life, often secondary to central nervous system involvement rather than direct nerve fiber damage.

Endocrine Effects: The Hidden Driver of Symptoms

Pituitary dysfunction is a major source of long-term complications in De Morsier syndrome. Hormone deficiencies can contribute to:

- Chronic fatigue

- Hypoglycemia

- Poor stress tolerance

- Delayed puberty or infertility

- Growth abnormalities

- Low blood pressure or electrolyte imbalances

Because endocrine symptoms may emerge gradually, they are sometimes mistaken for unrelated conditions unless the underlying diagnosis is recognized.

How De Morsier Syndrome Is Diagnosed

Diagnosis relies on a combination of clinical evaluation and imaging.

Common diagnostic steps include:

- Brain MRI to assess optic nerves, pituitary gland, and midline structures

- Comprehensive eye examination, often in infancy or early childhood

- Hormonal testing to evaluate pituitary function

- Developmental and neurological assessment

Genetic testing is not routinely diagnostic but may be used to rule out related syndromes.

Treatment and Management

There is no cure for De Morsier syndrome, but early and coordinated management significantly improves outcomes.

Treatment typically includes:

- Hormone replacement therapy for pituitary deficiencies

- Vision support, including low-vision services or adaptive tools

- Physical and occupational therapy for motor and balance issues

- Seizure management when present

- Educational and developmental support

Because symptoms vary widely, care is usually multidisciplinary, involving neurology, endocrinology, ophthalmology, and rehabilitation specialists.

Why Early Diagnosis Matters

Early recognition of De Morsier syndrome allows clinicians to prevent life-threatening hormonal crises, support visual and developmental needs, and reduce long-term complications. In children, timely intervention can improve growth, learning, and independence. In adults, it can clarify unexplained fatigue, visual limitations, or endocrine instability that may have gone undiagnosed for decades.

De Morsier syndrome is a reminder that neurological disorders are not always degenerative or dramatic at onset. Sometimes, they are quiet developmental conditions whose effects become clearer only with time. Recognizing the pattern is the first step toward effective care.

Further Reading

- Biological pathways leading to septo-optic dysplasia(SOD): a review

- Neurodevelopmental impairments in children with septo-optic dysplasia(SOD) spectrum conditions: a systematic review

- Septo-optic dysplasia(SOD): A Review

- Delineating septo-optic dysplasia.

- Septo-optic dysplasia(SOD): a review.

- Septo-optic dysplasia(SOD): a review.

- Septo-optic dysplasia: a literature review.