Imagine a perfectly folded sheet of paper—elegant, crisp, designed to do its job. Now imagine a crumpled version of that same sheet trying to convince all the others to crumple too. That’s the sinister nature of prions—proteins that have lost their shape and turned into contagious agents of destruction inside your nervous system.

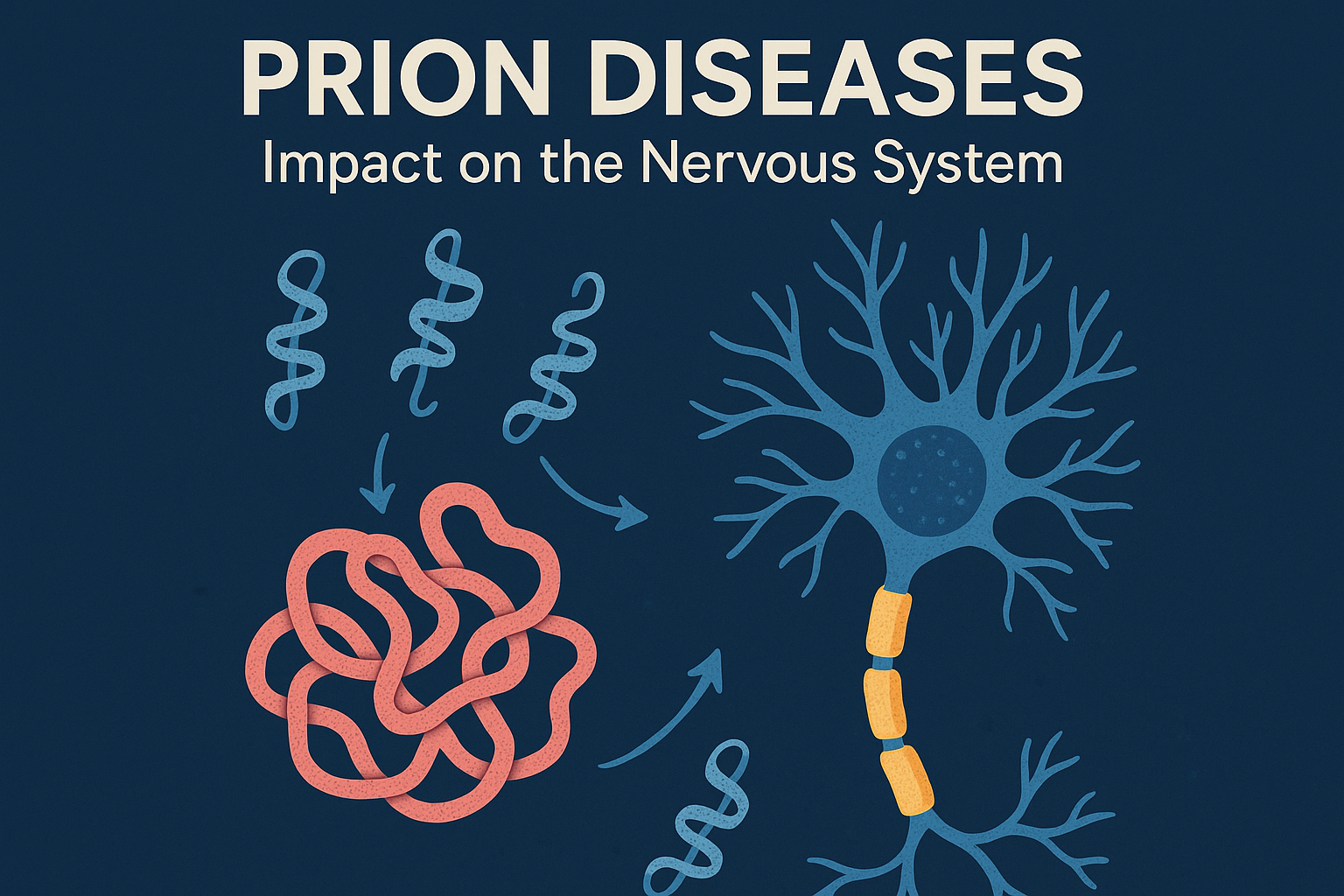

Prion diseases, also known as transmissible spongiform encephalopathies (TSEs), are rare but devastating neurological disorders. They are caused not by bacteria, viruses, or fungi—but by misfolded proteins. These rogue proteins don’t just malfunction; they recruit healthy proteins to misfold alongside them, setting off a destructive chain reaction in the brain and spinal cord.

When Proteins Go Rogue: Prion Diseases and Their Impact

The term “prion” is short for “proteinaceous infectious particle.” Normally, your body produces a harmless version of the prion protein (PrP), which is found on the surface of nerve cells. In prion diseases, this normal PrP undergoes a structural transformation, folding into a shape that’s not only useless—it’s toxic.

This misfolded prion protein is stubbornly resistant to the body’s usual cleanup systems. It clumps together and accumulates in brain tissue, causing cells to die. The result? Brain tissue develops sponge-like holes, which is why these diseases are called spongiform encephalopathies.

What Does This Have to Do with Neuropathy?

Neuropathy—nerve damage or dysfunction—can stem from many sources, from diabetes to chemotherapy. Prion diseases represent a rarer, more sinister cause. While most types of neuropathy affect the peripheral nerves (those outside the brain and spinal cord), prion diseases primarily attack the central nervous system (CNS).

However, prion-related neurodegeneration can have peripheral symptoms, especially early on. Patients may experience tingling, numbness, burning sensations, or coordination issues before more dramatic neurological symptoms emerge.

In particular, certain inherited prion diseases—such as Gerstmann-Sträussler-Scheinker syndrome (GSS)—present with neuropathy-like symptoms years before cognitive decline appears. This makes them easy to misdiagnose in the early stages.

Types of Prion Diseases

Here are the main prion diseases affecting humans:

1. Creutzfeldt-Jakob Disease (CJD)

The most well-known human prion disease. It typically causes rapid cognitive decline, balance problems, and involuntary muscle jerks. Neuropathy-like symptoms can appear early, such as sensory changes in the limbs.

- Sporadic CJD is the most common form, emerging without warning in people over 60.

- Variant CJD is linked to consuming meat from cattle infected with “mad cow disease” (bovine spongiform encephalopathy).

2. Gerstmann-Sträussler-Scheinker (GSS) Syndrome

A genetic prion disease, GSS may begin with symptoms resembling peripheral neuropathy—tingling, muscle weakness, or unsteady gait. These signs can appear years before dementia or full-blown motor symptoms.

3. Fatal Familial Insomnia (FFI)

This rare inherited condition starts with sleep disturbances, but quickly escalates to problems with the autonomic nervous system (like heart rate and blood pressure), hallucinations, and severe neurological decline. Though not classified as a peripheral neuropathy, its widespread impact often causes neuropathic symptoms.

4. Kuru

Once found among the Fore people of Papua New Guinea, Kuru was spread through ritualistic cannibalism. Patients developed tremors, balance issues, and neuropathy-like limb symptoms before cognitive failure.

How Do You Get a Prion Disease?

In most cases, you don’t. Prion diseases are extremely rare. Most arise spontaneously (sporadic CJD), are inherited (via gene mutations), or—rarely—transmitted through contaminated surgical tools or infected tissue (e.g., in organ transplants or corneal grafts).

You cannot catch a prion disease through casual contact, breathing the same air, or touching someone with the condition. That said, the infectious nature of prions is a major concern in neurosurgery and transplant medicine due to their resistance to standard sterilization techniques.

Diagnosis and Detection

Diagnosing prion diseases is a challenge. Many early symptoms mimic more common conditions—depression, balance issues, neuropathy, or Parkinson’s disease. Definitive diagnosis often requires advanced imaging (like MRI), cerebrospinal fluid analysis, or genetic testing. In some cases, a brain biopsy or autopsy confirms the diagnosis.

Doctors may also use EEG (electroencephalogram) to detect characteristic brain wave abnormalities or RT-QuIC, a newer lab test that can detect prion protein in cerebrospinal fluid or other tissues with high sensitivity.

Treatment and Prognosis

Here’s the hard truth: There is no cure for prion diseases. Once symptoms appear, the condition typically progresses rapidly. Most patients with sporadic CJD, for example, pass away within a year.

That said, early recognition—especially in hereditary forms like GSS—can help patients and families prepare, manage symptoms, and participate in clinical trials. Researchers are investigating antibodies, gene-silencing therapies, and drugs that may slow prion accumulation.

Why It Matters for Neuropathy Patients

Prion diseases are rare, but understanding them highlights a powerful truth: Not all neuropathies are what they seem. When tingling, burning, or numbness is accompanied by memory issues, personality changes, or sleep disturbances, it’s worth digging deeper.

For clinicians, prion diseases serve as a reminder to think broadly. For patients, they offer a glimpse into how delicate and interwoven our nervous systems really are.

Even a single misfolded protein can bring down the whole orchestra of the brain—and that’s both terrifying and awe-inspiring. But knowledge is power, and awareness can lead to faster diagnosis, better care, and—someday—a cure.