Imagine walking on gravel—barefoot—every day. For many people with Fabry’s disease, this sensation isn’t imaginary. It’s part of a painful reality where nerve fibers misfire, delivering sharp, burning pain, especially in the hands and feet. But Fabry’s disease isn’t just about nerve pain. It’s a complex, inherited condition that affects multiple organs and systems, often hiding in plain sight for years.

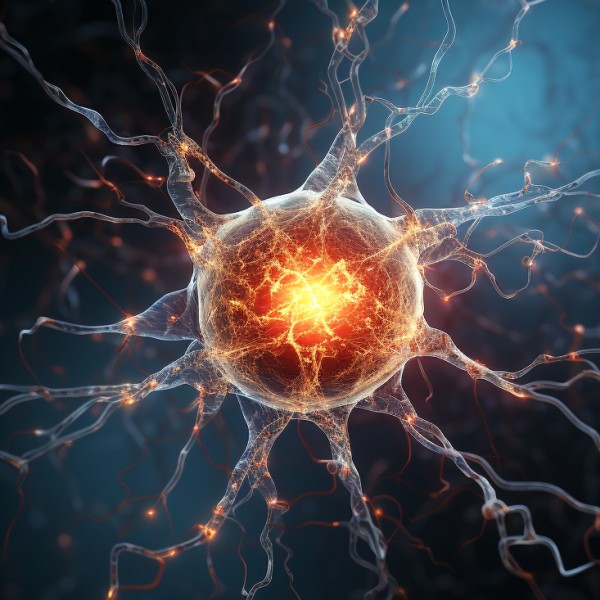

Fabry’s disease (also called Anderson–Fabry disease) is one of the rare causes of neuropathy, but its impact extends far beyond the nerves. It is a progressive, X-linked lysosomal storage disorder that disrupts how the body breaks down a specific type of fat. That fat—called globotriaosylceramide, or GL-3 for short—builds up inside cells and damages tissues throughout the body, including the nervous system, kidneys, heart, and skin.

Let’s take a closer look at what causes Fabry’s, how it affects people (especially in the context of nerve pain), and what treatments are available.

What Causes Fabry’s Disease?

Fabry’s disease is caused by mutations in the GLA gene on the X chromosome. This gene provides instructions for making an enzyme called alpha-galactosidase A. When the enzyme doesn’t work properly—or is missing altogether—GL-3 begins to accumulate in cells, particularly in the walls of blood vessels and nerve cells.

Because it’s X-linked, Fabry’s disease tends to affect males more severely. Females can still be affected, but symptoms may be milder or show up later in life. However, many women with Fabry’s disease do experience significant complications and are increasingly recognized as underdiagnosed.

Fabry and Neuropathy: The Burning Clue

One of the earliest signs of Fabry’s disease is a form of small fiber neuropathy. This manifests as burning pain, tingling, or numbness in the hands and feet. The pain can be episodic (known as Fabry crises) or chronic. For some children and teenagers, these symptoms appear as early as age 5 or 6 and are often misattributed to growing pains or behavioral issues.

Heat, fever, stress, or exercise can trigger episodes. Patients might avoid playing outside or participating in sports, not because they don’t want to—but because the pain becomes unbearable. As they get older, some patients experience reduced sensation in the skin, making it harder to detect temperature changes or minor injuries.

In Fabry’s disease, nerve pain is often a clue—but rarely the full story.

Other Symptoms and Effects

Fabry’s disease is systemic, which means it affects the whole body. Common signs and symptoms include:

- Angiokeratomas: tiny, dark red skin spots, often found in clusters around the lower trunk.

- Hypohidrosis or anhidrosis: reduced or absent sweating, which can lead to overheating.

- Corneal verticillata: whorl-like patterns in the cornea, usually seen only on eye exam.

- Gastrointestinal issues: abdominal pain, nausea, or bloating, often confused with IBS.

- Kidney involvement: proteinuria, decreased kidney function, and eventual kidney failure.

- Heart complications: thickened heart muscle, arrhythmias, and increased risk of stroke.

- Hearing loss or tinnitus.

Because symptoms vary widely and can mimic more common conditions, Fabry’s disease is often misdiagnosed—or missed entirely. It’s not uncommon for patients to go years or decades without a correct diagnosis.

How To Diagnose Fabry’s Disease

Diagnosis begins with clinical suspicion—especially if a person has unexplained nerve pain, kidney issues, or cardiac problems starting at a young age. Family history is another important clue.

Diagnostic tests include:

- Blood test to measure alpha-galactosidase A activity (more reliable in males).

- Genetic testing to detect GLA mutations.

- Urine tests to measure GL-3 levels.

- Skin biopsy or nerve testing (in cases with unclear neuropathy).

In females, enzyme levels may appear normal even if they carry the mutation, making genetic testing essential.

Treatment Options

Although Fabry’s disease is chronic and progressive, there are treatments that can slow its course and improve quality of life.

- Enzyme Replacement Therapy (ERT): Synthetic versions of alpha-galactosidase A are infused into the bloodstream every two weeks. This can reduce pain, slow kidney decline, and improve heart health.

- Chaperone Therapy: For some specific mutations, a small molecule drug (migalastat) helps stabilize the enzyme and improve its function.

- Pain Management: Neuropathic pain is treated with medications like gabapentin, pregabalin, or duloxetine—though results vary.

- Supportive care: Includes blood pressure control, kidney monitoring, hearing aids, and lifestyle modifications.

- Gene therapy: Still in clinical trials, but holds promise for long-term correction.

Why Early Diagnosis Matters

The earlier Fabry’s disease is diagnosed, the better the outcomes. Early intervention can delay kidney damage, reduce cardiac complications, and improve pain control. In children, this means fewer missed school days, better social engagement, and less psychological stress.

For adults, it can mean the difference between managing symptoms and facing organ failure. And for families, early diagnosis allows for genetic counseling, screening of relatives, and informed decisions.

Fabry’s disease reminds us that nerve pain isn’t always caused by diabetes, injury, or age. Sometimes, it’s the body’s early alarm bell for something deeper. For neuropathy patients, especially those with unexplained burning pain, Fabry’s deserves a spot on the differential.